A technical account of Anglo-Scottish Greenland Expedition is featured in 2009 American Alpine Journal: The World’s Most Significant Climbs.

ISBN: 978-1-933056-09-8

Knud Rasmussens Land, 2006 ascents. In August 2006 Jennifer Escott, Jonathan Hunter, Nick Mills, and I visited Knud Rasmussens Land, landing on the icecap at N 69°38.9′, W 27°44.0′.

This spot was the base camp for an out-going expedition from the Brathay Exploration Group, and we took over some of their vital pieces of kit, such as satellite phone and shotgun.

We planned to divide the expedition into three phases of roughly a week each: one on the icecap, exploring an impressive massif near the drop-off; one pulk-pulling across the icecap; and the third attempting unclimbed peaks around the glacier to the south, down from the icecap. Peaks on the icecap (nunataks) generally rise only a few hundred meters above the ice. Peaks on the lower glacier, although of similar altitude, generally involve climbs of much greater length and commitment, with exposed ridges of snow and friable basalt. From the air these peaks appeared quite challenging.

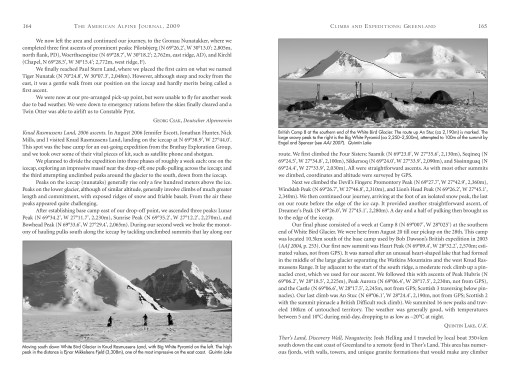

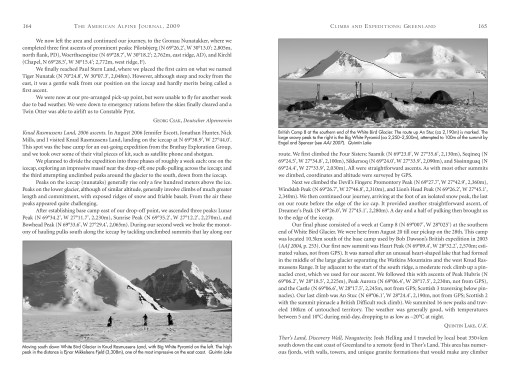

Moving south down White Bird Glacier in Knud Rasmussens Land, with Big White Pyramid on the left. The high peak in the distance is Ejnar Mikkelsens Fjeld (3,308m), one of the most impressive on the east coast.

After establishing base camp east of our drop-off point, we ascended three peaks: Lunar Peak (N 69°34.2′, W 27°11.7′, 2,230m), Sunrise Peak (N 69°35.2′, W 27°12.2′, 2,270m), and Bowhead Peak (N 69°33.6′, W 27°29.4′, 2,065m). During our second week we broke the monotony of hauling pulks south along the icecap by tackling unclimbed summits that lay along our route. We first climbed the Four Sisters: Saamik (N 69°23.0′, W 27°35.6′, 2,130m), Seqineq (N 69°24.5′, W 27°34.8′, 2,100m), Sikkersoq (N 69°24.0′, W 27°33.9′, 2,090m), and Sissinnguaq (N 69°24.4′, W 27°33.9′, 2,030m). All were straightforward ascents. As with most other summits we climbed, coordinates and altitude were surveyed by GPS.

Next we climbed the Devil’s Fingers: Promontory Peak (N 69°27.7′, W 27°42.9′, 2,360m), Windslab Peak (N 69°26.7′, W 27°46.8′, 2,310m), and Lion’s Head Peak (N 69°26.2′, W 27°45.1′, 2,340m). We then continued our journey, arriving at the foot of an isolated snow peak, the last on our route before the edge of the ice cap. It provided another straightforward ascent, of Dreamer’s Peak (N 69°26.0′, W 27°45.1′, 2,280m). A day and a half of pulking then brought us to the edge of the icecap.

British Camp 8 at the southern end of the White Bird Glacier. The route up An Stuc (ca 2,190m) is marked. The large snowy peak to the right is the Big White Pyramid (ca 2,250–2,500m), attempted to 100m of the summit by Engel and Spencer (see AAJ 2007).

Our final phase consisted of a week at Camp 8 (N 69°007′, W 28°025′) at the southern end of White Bird Glacier. We were here from August 20 till our pickup on the 28th. This camp was located 10.5km south of the base camp used by Bob Dawson’s British expedition in 2003 (AAJ 2004, p. 253). Our first new summit was Heart Peak (N 69°09.4′, W 28°32.2′, 2,570m; estimated values, not from GPS). It was named after an unusual heart-shaped lake that had formed in the middle of the large glacier separating the Watkins Mountains and the west Knud Rasmussens Range. It lay adjacent to the start of the south ridge, a moderate rock climb up a pinnacled crest, which we used for our ascent. We followed this with ascents of Peak Hubris (N 69°06.2′, W 28°18.5′, 2,225m), Peak Aurora (N 69°06.4′, W 28°17.5′, 2,230m, not from GPS), and the Castle (N 69°06.6′, W 28°17.5′, 2,245m, not from GPS; Scottish 3 traversing below pinnacles). Our last climb was An Stuc (N 69°06.1′, W 28°24.4′, 2,190m, not from GPS; Scottish 2 with the summit pinnacle a British Difficult rock climb). We summited 16 new peaks and travelled 100km of untouched territory. The weather was generally good, with temperatures between 5 and 10°C during mid-day, dropping to as low as –20°C at night.

QUINTINLAKE, U.K.

View Expedition report here Download PDF of feature here

Gallery of arctic landscape photographs from the expedition here

Buy 2009 American Alpine Journal from Amazon UK here