Alice Ayres (Natalie Portman) & Dan Woolf (Jude Law) in front of Memorial to Heroic Self Sacrifice in the movie Closer

Postman's Park located between St Martin’s le Grand and King Edward Street in the City of London (Photo: Quintin Lake)

Alice Ayres (Natalie Portman) & Dan Woolf (Jude Law) enter Postman's park in the movie Closer

Postman's Park view of the loggia that makes up the Memorial to Heroic Self Sacrifice , City of London (Photo: Quintin Lake)

Dan Woolf (Jude Law) returns to the Memorial in Postman's Park at the end of the film Closer

Memorial to Heroic Self Sacrifice Loggia in Postman's Park, City of London (Photo: Quintin Lake)

"In commemoration of Heroic Self Sacrifice" Postman's Park, City of London (Photo: Quintin Lake)

Arrangement of the tiles in the Memorial to Heroic Self Sacrifice, Postman's Park, City of London (Photo: Quintin Lake)

Statue of George Frederic Watts by T. H. Wren inscription reads "The Utmost for the Highest" "In memorial of George Frederic Watts, who desiring to honour heroic self-sacrifice placed these records here" (Photo: Quintin Lake)

1900 tile by William De Morgan. one of the first to be installed "Walter Peart, Driver and Harry Dean, Fireman of the Windsor Express on July 18 1898 Whilst being scalded and burnt sacrificed their lives in saving the train" (Photo: Quintin Lake)

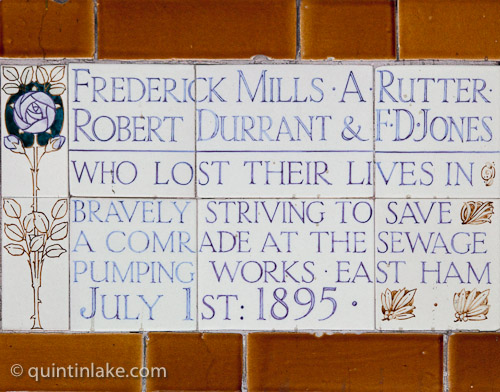

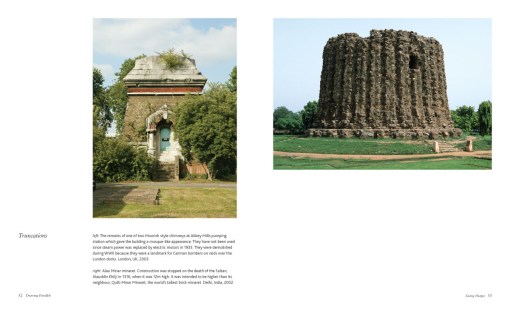

1902 tile by Royal Doulton "Frederick Mills · A Rutter Robert Durant & F D Jones Who lost their lives in bravely striving to save a comrade at the Sewage Pumping Works East Ham July 1st 1895" (Photo: Quintin Lake)

1902 tile by William De Morgan "Alice Ayres Daughter of a bricklayer's labourer Who by intrepid conduct saved 3 children from a burning house in Union Street Borough at the cost of her own young life April 24 1885" In the movie Closer Alice Ayres is played by Natalie Portman and Dan Woolf by Jude Law who notices this tile which features in the film. (Photo: Quintin Lake)

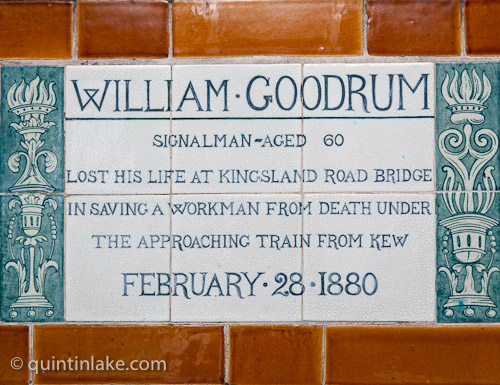

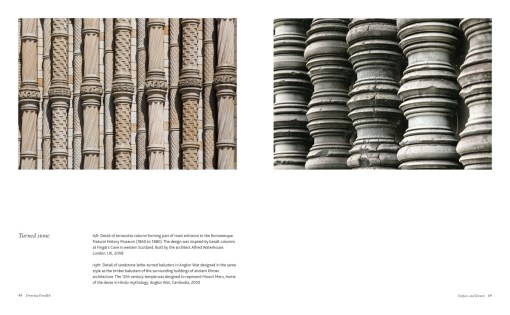

1905 tile by William De Morgam "William Goodrum Signalman · Aged 60 Lost his life at Kingsland Road Bridge in saving a workman from death under the approaching train from Kew February 28 1880" (Photo: Quintin Lake)

1908 tile by Royal Doulton "Thomas Simpson Died of exhaustion after saving many lives from the breaking ice at Highgate Ponds Jan 25 1885" (Photo: Quintin Lake)

1930 tile by Royal Doulton "P.C. Percy Edwin Cook Metropolitan Police Voluntarily descended high-tension chamber at Kensington to rescue two workmen overcome by poisonous gas" (Photo: Quintin Lake)

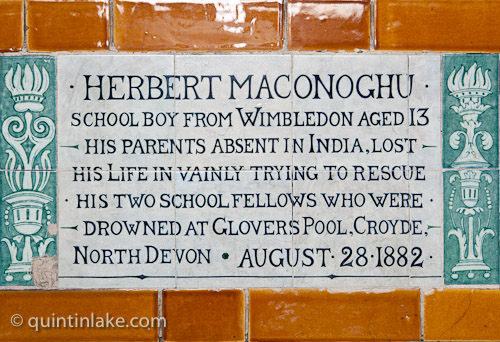

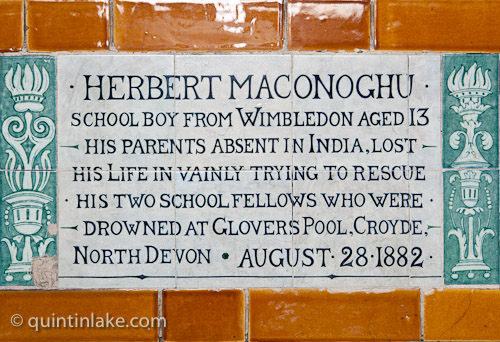

1931 tile by Fred Passenger "Herbert Maconoghu School boy from Wimbledon aged 13 His parents absent in India, lost his life in vainly trying to rescue his two school fellows who were drowned at Glovers Pool, Croyde, North Devon August 28 1882" (Photo: Quintin Lake)

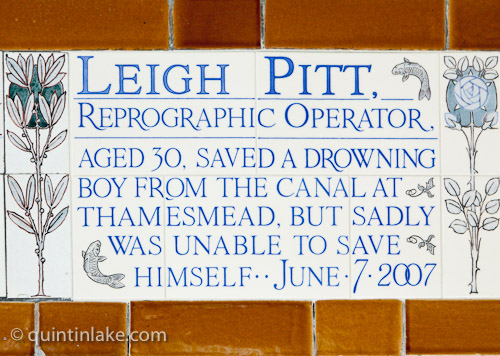

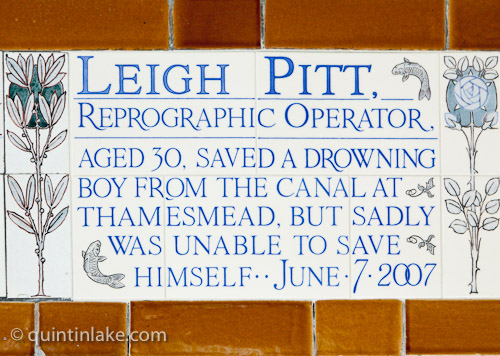

the most recent 2009 tile by Craven Dunnill Jackfield Ltd "Leigh Pitt Reprographic operator Aged 30, saved a drowning boy from the canal at Thamesmead, but sadly was unable to save himself" (Photo: Quintin Lake)

Postman’s Park is hidden away park in central London, a short distance north of St Paul’s Cathedral. Bordered by Little Britain, Aldersgate Street, King Edward Street, and the site of the former head office of the General Post Office (GPO), it is one of the largest parks in the City of London, the walled city which gives its name to modern London. A shortage of space for burials in London meant that corpses were often laid on the ground and covered over with soil instead of being buried, and thus Postman’s Park, built on the site of former burial grounds, is significantly elevated above the streets which surround it. It is best known as the location of the Memorial to Heroic Self Sacrifice.

Opened in 1880 on the site of the former churchyard and burial ground of St Botolph’s Aldersgate church, it expanded over the next 20 years to incorporate the adjacent burial grounds of Christ Church Greyfriars and St Leonard, Foster Lane, as well as the site of housing demolished during the widening of Little Britain in 1880, the ownership of which became the subject of a lengthy dispute between the church authorities, the General Post Office, the Treasury, and the City Parochial Foundation. The park’s name reflects its popularity amongst workers from the nearby GPO’s headquarters.

In 1900, the park became the location for George Frederic Watts’s Memorial to Heroic Self Sacrifice (also known as the Wall of Heroes), a memorial to ordinary people who died saving the lives of others and might otherwise have been forgotten, in the form of a loggia and long wall housing ceramic memorial tablets. At the time of its opening, only four of the planned 120 memorial tablets were in place, with a further nine tablets added during Watts’s lifetime. Following Watts’s death in 1904, his wife Mary Watts took over the management of the project and oversaw the installation of a further 35 memorial tablets in the following four years, as well as a small monument to Watts. However, disillusioned with the new tile manufacturer and with her time and money increasingly occupied by the running of the Watts Gallery, Mary Watts lost interest in the project and only five further tablets were added during her lifetime.

Although Watts’s plans for the memorial had envisaged names inscribed on the wall, in the event the memorial was designed to hold panels of hand-painted and glazed ceramic tiles. Watts was an acquaintance of William De Morgan, at that time one of the world’s leading tile designers, and consequently found them easier and cheaper to obtain than engraved stone.

In 1972, key elements of the park, including the Memorial to Heroic Self Sacrifice, were grade II listed to preserve their character. Following the 2004 film Closer, based on the 1997 play Closer by Patrick Marber, Postman’s Park experienced a resurgence of interest; key scenes of both were set in the park itself. In June 2009 the Diocese of London added a new tablet to the Memorial in the style of the Royal Doulton tiles for Leigh Pitt, a print technician from Surrey, had died on 7 June 2007 rescuing nine-year-old Harley Bagnall-Taylor who was drowning in a canal in Thamesmead. This tile the first new addition for 78 years and the 54th tablet

These photographs were commissioned by Thames & Hudson / View Pictures for an upcoming book on the architecture of the City of London

View more images of Postman’s Park and all 54 tiles in the Memorial to Heroic Self Sacrifice, London here

Photography © Quintin Lake, 2010