“Architecture [is] a theatre stage setting where the leading actors are the people, and to dramatically direct the dialogue between these people and space is the technique of designing.”

Kisho Kurokawa

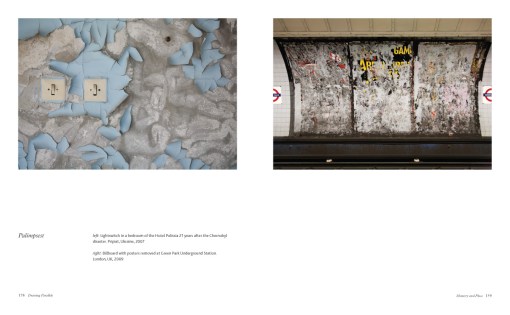

Public places and buildings have the added dimension of acting as arenas for our lives. In the virtual era we have a heightened awareness of the nature of illusion, of the fact that we are at one and the same time both observing and participating.We see buildings as the backdrop to history and human drama, no longer as organic wholes to which we are connected. In a global village we become tourists and visitors to the sets of a world of other cultures. The photographer, always the contriver and exposer of visual illusion, is attuned to this particularly contemporary phenomenon. Cities and places continually present new ironies, making the observer constantly aware of the layers of transparency. People become orchestrated crowds, and architecture a grand theatrical set, yet individuals are still glimpsed, asserting the defiantly human amongst the towering forests of forms.

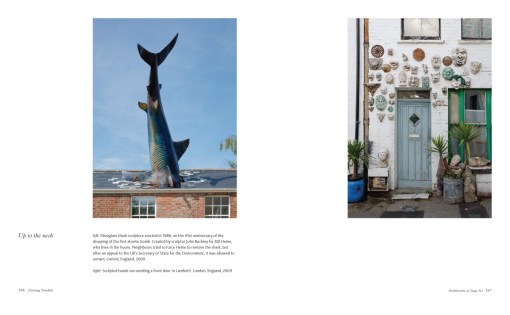

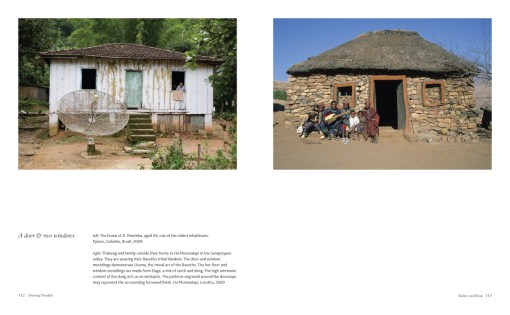

Up to the neck

left: Fibreglass shark sculpture erected in 1986, on the 41st anniversary of the dropping of the first atomic bomb. Created by sculptor John Buckley for Bill Heine, who lives in the house. Neighbours tried to force Heine to remove the shark, but after an appeal to the UK’s Secretary of State for the Environment, it was allowed to remain. Oxford, England, 2009

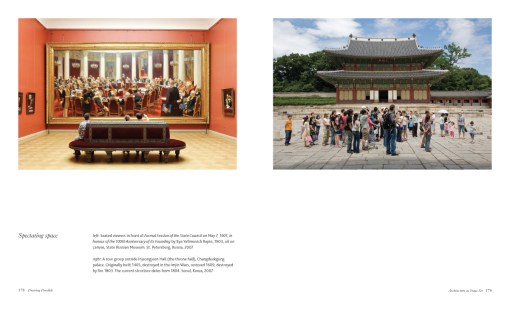

right: Sculpted heads surrounding a front door in Lambeth. London, England, 2009

Click on image to enlarge or download Print Res (300dpi) PDF of this spread here

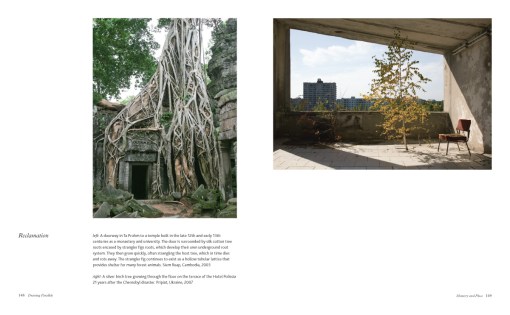

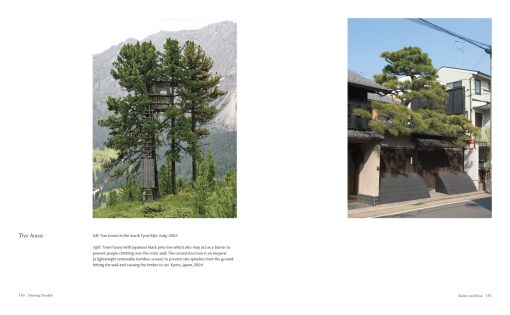

Spectating space

left: Seated viewers in front of Formal Session of the StateCouncil onMay 7, 1901, in honour of the 100th Anniversary of Its Founding by Ilya Yefimovich Repin, 1903, oil on canvas, State Russian Museum. St. Petersburg, Russia, 2007

right: A tour group outside Injeongjeon Hall (the throne hall), Changdeokgung palace. Originally built 1405, destroyed in the ImjinWars, restored 1609, destroyed by fire 1803. The current structure dates from 1804. Seoul, Korea, 2007

Click on image to enlarge or download Print Res (300dpi) PDF of this spread here

Extract from my architectural photography book: Drawing Parallels, Architecture Observed

Text & Photography © Quintin Lake, 2009